Today I’ll share a few photo highlights from last Friday’s trip: a field review of the new geological map of the Timberville, VA quadrangle, by Matt Heller and Randy Orndorff. I’ve previously shared three 360° panoramic “spherical photos” from the trip. Today, the pictures will be the old-fashioned kind. One of the first stops was to a fault zone, where Cambrian carbonates were thrust over shales of inferred Ordovician age. Here’s a look at some of the shales:

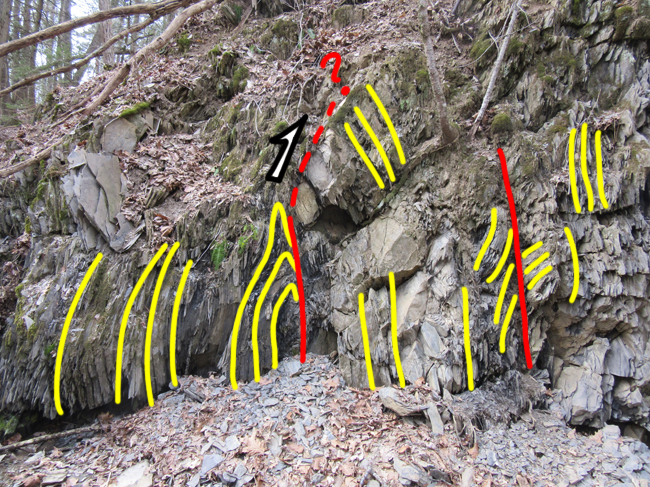

Tracing out bedding (in yellow) reveals some structural complexity, with tight folding and probable faulting, as seen here:

On one slab of shale, I found a graptolite fossil:

Contrast dialed up a bit so it’s easier to see:

Outlined:

I passed this on to the mappers in case it could help identify the unit more precisely. (Edinburg Formation?)

Nearby, there were several of these striking scarlet cup fungi:

Here’s the fault surface itself, with Randy pointing out deformed rocks in the footwall:

Though this fault is expressed topographically as a “wall,” it’s not a scarp. This is a case of differential weathering, where the footwall shales are more easily etched away by the stream, and so the hanging wall carbonates stand proud of the landscape.

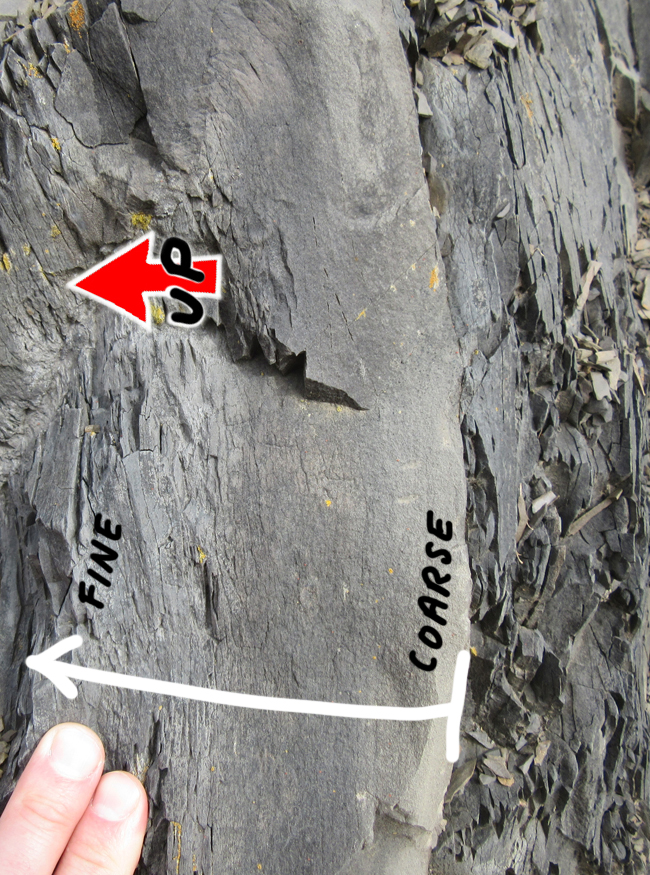

Our next stop was at Brock’s Gap, where we looked at the transition from the late Ordovician Martinsburg Formation (turbidites) into the overlying Oswego Group sandstones. Here’s a nice example of a graded bed in the Martinsburg:

Because graded bedding looks different at the bottom of the bed than the top, it can be utilized as a ‘geopetal’ indicator – a clue about ‘which way was up’ when these strata were deposited. This is very useful thing to know when you’re doing geologic mapping. At Brock’s Gap, the strata are vertical or slightly overturned, younging to the west.

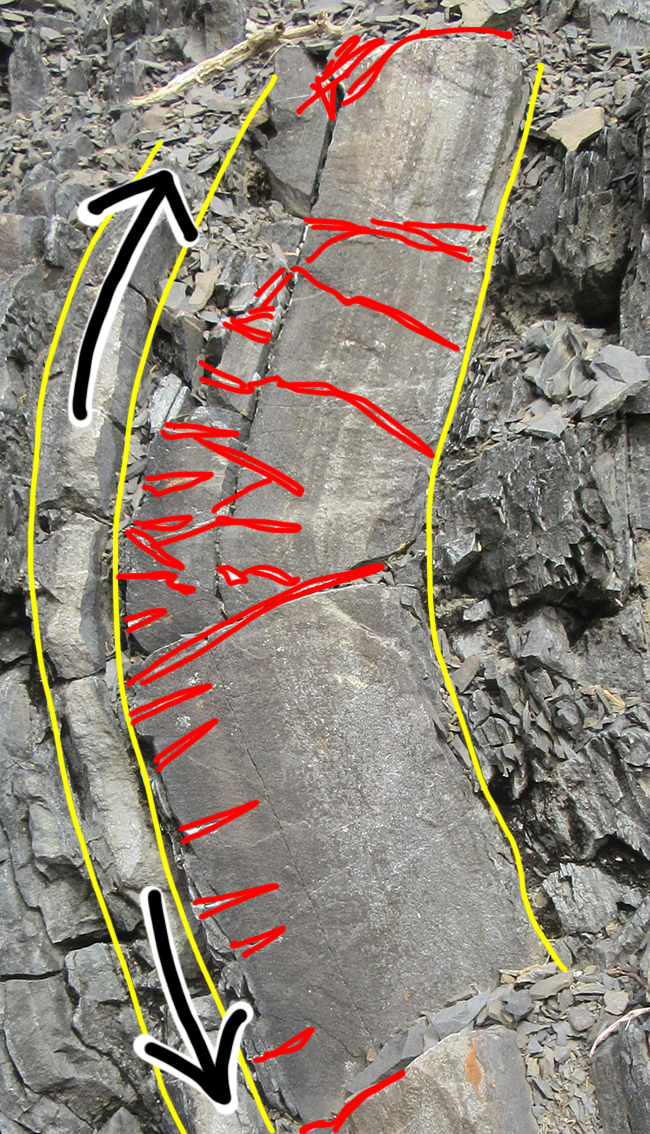

There were tectonic structures to behold, too. Here’s a folded turbidite, showing more fracturing on the outer part of the arc than the inside.

…Zooming in…

This is typical of the folding of relatively competent layers – outer arc extension is accommodated partially by cracking. The cracks are subsequently filled with mineral deposits – and then they are veins.

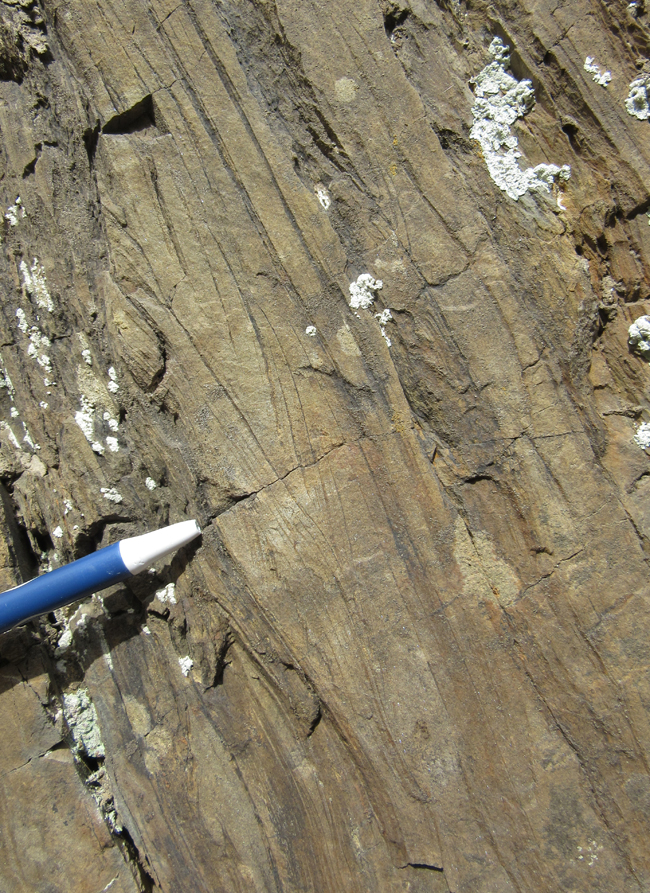

Some Skolithos were spotted in the Oswego:

We then climbed up onto North Mountain, and were examining slices of rock that had galloped all over each other (“horses”) along the North Mountain Fault system. I learned a new clue for locating a fault in this heavily vegetated land: look for travertine suddenly appearing the creeks!

Travertine is freshwater limestone with a distinctive spongy appearance. It’s a common feature in creeks in Virginia’s Valley & Ridge province where the creek gains some of its discharge via the groundwater, and the groundwater has been in the business of dissolving subterranean limestone before flowing out at the surface. Faults act as preferential fluid flow pathways, shunting this CaCO3-rich water into the creeks, where agitation makes it precipitate out, building up ledges like the ones in the photo above.

Next up: Devonian mudrocks and turbidites…

Here’s a fold in a unit that I think we agreed must be the Marcellus/Needmore:

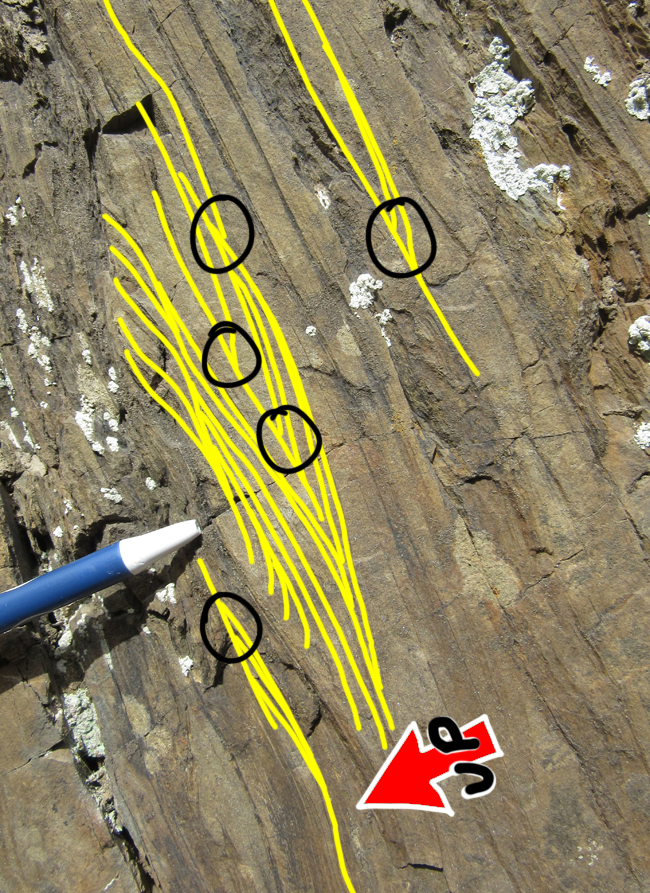

We entered the Brallier Formation, and saw some nice examples there of overturned cross-bedding, indicating these strata have been tectonically inverted.

Here’s the same photo with bedding annotated in yellow, and several spots circled in black where you can see clear truncating relationships:

Another example, on a fresher surface:

DGMR geologist Anne Witt serves as a sense of scale for a folded and faulted section of Brallier shales:

I think I see at least three small “horses” (ponies??) there – with nice drag folds on the top of the one directly in front of Anne:

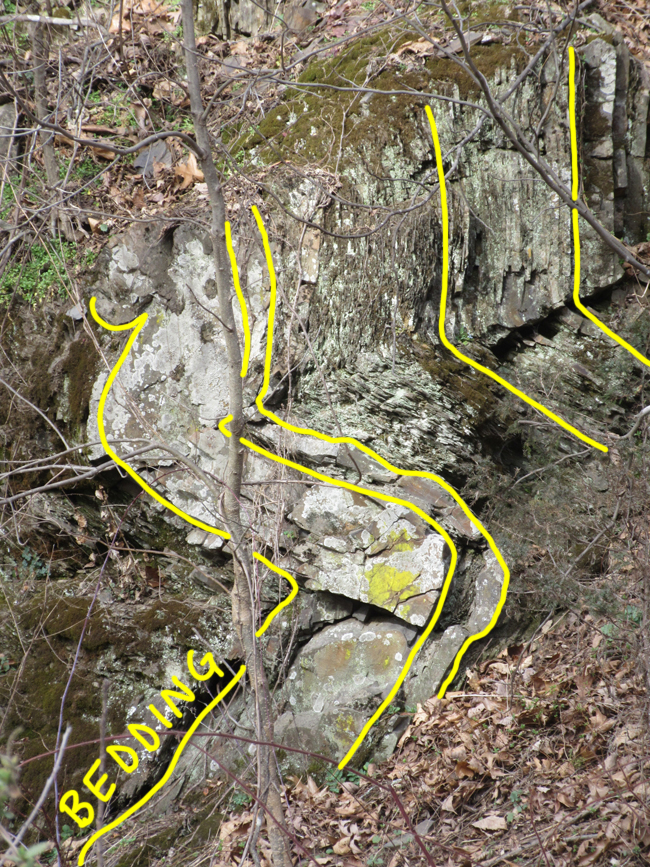

Another Brallier stop showed a wall of folded turbidites:

These folds had horizontal axial surfaces, so we would classify them as “recumbent” (tectonically “lying on their sides”):

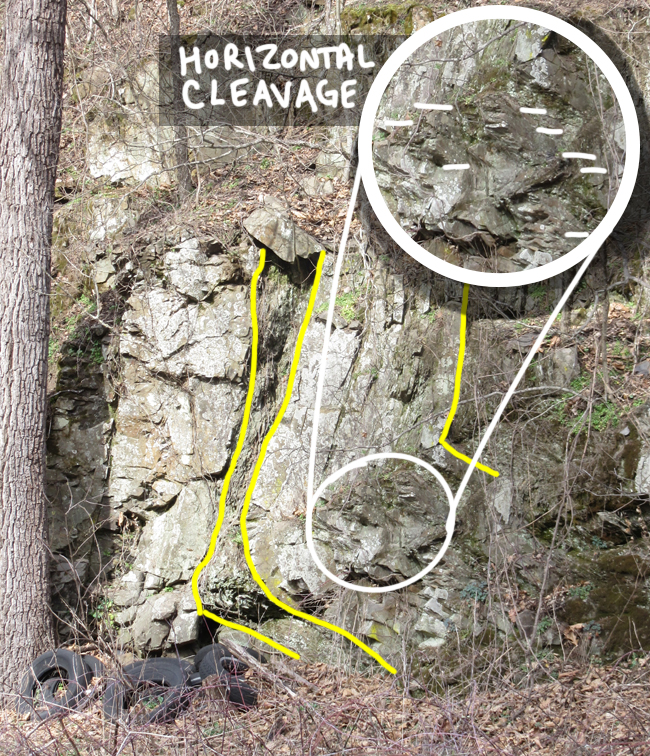

Another one, with a breeding colony of Appalachian tires for scale:

As I was writing up this blog post, I noticed that cleavage also has a ~horizontal orientation:

Finally, we climbed out of the Devonian (Acadian) “flysch” and into the “molasse”: redbeds of the Foreknobs or Hampshire Formation, though it was hard to make the call which one it was at this particular outcrop. There were some nice ripple marks there, though.

They were so sweet that I willingly braved a thicket of thorns on an unstable shaley slope in order to get the 360° panorama of them in close-up.

![IMG_2638]() (Last two photos by Nathan from UVA)

(Last two photos by Nathan from UVA)

All told, it was an excellent day in the field – as you can tell from the ancillary qualities of these images, the weather was sunny and mild, and there was minimal vegetation to obscure the lovely geology.

Thanks to Matt and Randy for organizing the field review, and letting me tag along!